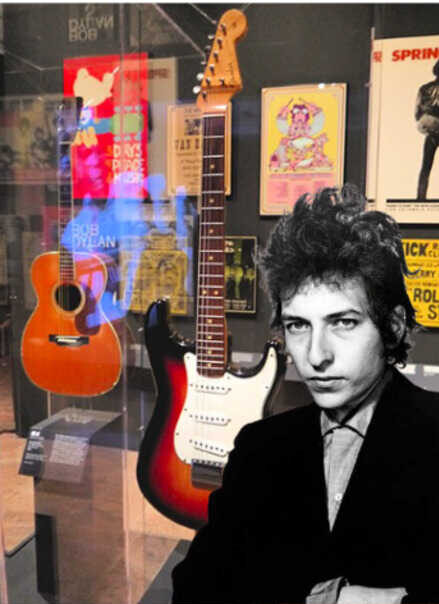

Bob Dylan’ photo by Daniel Kramer, 1965

Montage: Luli Delgado

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

In the jingle-jangle morning I’ll come following you.

I have always loved that line. It has haunted me since I first heard it, shimmering with promise and uncertainty. For years I thought it must conceal some deeper meaning — a code or hidden message — but now I realise it doesn’t mean anything at all. The words are the meaning. They are beautiful, melodic, alliterative, compelling.

We have all woken in the jingle-jangle morning, unsure what the day will bring, and felt that sudden urge to follow our dreams, our lover, our destiny.

The line closes the chorus of Mr. Tambourine Man:

Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me

I’m not sleepy and there is no place I’m going to.

Hey! Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me

In the jingle-jangle morning I’ll come following you.

When Mr. Tambourine Man appeared in March 1965 as the opening track on the acoustic side of Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home, it was unlike anything the world had heard. The Byrds recorded their own version a month later, transforming Dylan’s dreamlike poetry into a glistening anthem. With its chiming twelve-string guitars and bright percussion, The Byrds’ Mr. Tambourine Man became the blueprint for folk rock and what came to be known as jangle pop — a sound that fused the lyrical intimacy of folk with the electric pulse of the new age.

A year earlier, The Beatles were still writing boy-loses-girl love songs — I Want to Hold Your Hand, Please Please Me, Can’t Buy Me Love. Dylan’s Hard Rain, Blowin’ in the Wind, and The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll changed everything. They made it possible for pop to grow up, for words to matter. Without Dylan there would be no Imagine, no Yesterday, no While My Guitar Gently Weeps.

Dylan began sketching Mr. Tambourine Man in 1964 on a road trip to New Orleans for Mardi Gras. You can almost hear the parade in the distance: the mystery tramp of the drums, the jingle-jangle chatter of a ragged clown dressed as a monk, the rhythm of a city spinning on its own dream. The song moves like that parade — shifting, hypnotic, filled with faces half-seen through the haze.

Though you might hear laughing, spinning, swinging madly across the sun,

It’s not aimed at anyone,

It’s just escaping on the run.

He sang it live on 17 May 1965 at London’s Royal Festival Hall. I was there — four months from my eighteenth birthday, still at school, waiting for exam results and not quite sure who I was meant to become. That night changed me.

A few weeks later, I saw a notice in a local paper: “Trainee reporter wanted — Isle of Thanet Gazette.” I applied, was hired, and began in August 1965 — the same week The Byrds’ Mr. Tambourine Man reached No. 1.

It felt like a sign. My own jingle-jangle morning had arrived, and I’ve been following the song ever since.