“Hilliard, soon nicknamed the “Boxing Parson,” stood out. Jason Gurney, who fought alongside him, remembered an ex-Anglican priest who could parody blessings “in the name of Marx,” but who in battle was fearless, leading small squads in desperate counterattacks…”

Fuente:https://en.wikipedia.org/

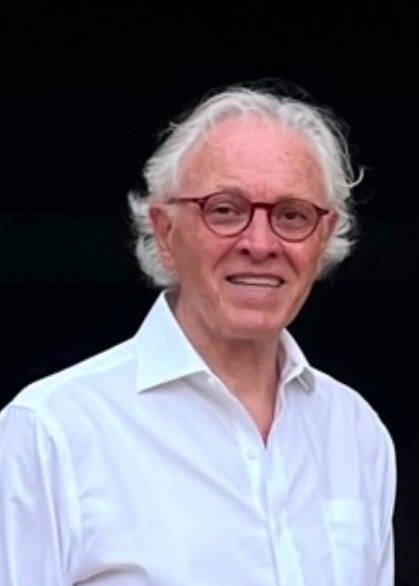

In April 1904, in Killarney, County Kerry, Robert Martin Hilliard was born into the comforts of a middle-class family. He would live only 32 years, but in that brief span he became many men: scholar, boxer, clergyman, journalist, communist, soldier. His story is a parable of a turbulent age.

Hilliard excelled at Trinity College, Dublin, and fought in the bantamweight division of the 1924 Paris Olympics. He married his childhood sweetheart, Rosemary, fathered four children, and entered the Church of Ireland ministry in Belfast. But he was restless. Poverty on the streets, the rise of fascism in Europe, the limits of pulpit sermons—these gnawed at him. By 1936 he had left the ministry, moved to London, and joined the Communist Party.

That same summer, Spain erupted. Franco and his generals rose against the Republic; workers and peasants resisted. To Hilliard, Spain was the frontier of his generation’s struggle: fascism must be stopped there, or it would spread everywhere. He joined the International Brigades and trained with the British Battalion in the camps at Albacete.

Their first action was at Jarama in February 1937. Franco’s Army of Africa sought to cut Madrid’s lifeline to Valencia. The British Battalion—barely 600 strong, poorly armed—was ordered to seize a ridge that became Suicide Hill. Veterans recalled machine-gun fire tearing through the volunteers, bodies scattered in the scrub, tanks rolling over the wounded. Barely a 100 survived unscathed.

In that furnace, Hilliard, soon nicknamed the “Boxing Parson,” stood out. Jason Gurney, who fought alongside him, remembered an ex-Anglican priest who could parody blessings “in the name of Marx,” but who in battle was fearless, leading small squads in desperate counterattacks.

He was struck in the neck, evacuated to Castellón, and died ten days later on 22 February 1937. He was buried in the cemetery there, his remains later lost when Franco’s regime consigned Republican and International Brigade dead to mass graves.

What endures is not victory—the Republic fell in 1939—but symbolism. The International Brigades, poorly armed yet resolute, held Madrid when it might have collapsed. Their sacrifice became a beacon. Orwell called Spain “the central event of the 1930s.” In Christy Moore’s ballad Viva la Quince Brigada, Hilliard’s name is sung: “Bob Hilliard was a Church of Ireland pastor; From Killarney ‘cross the Pyrenees he came…”