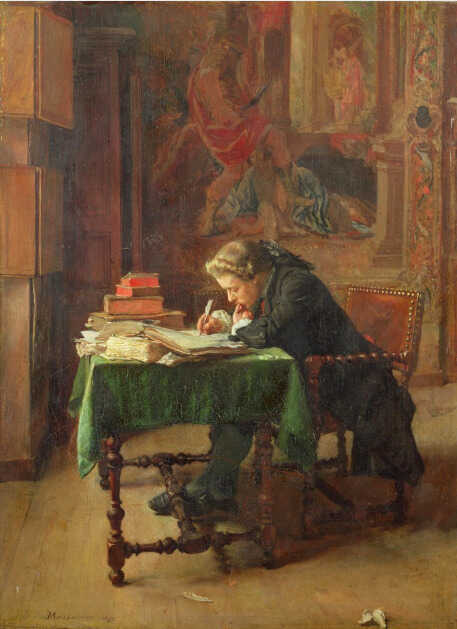

Joven escritor, 1852

Fuente: https://www.meisterdrucke.uk/

If you have a box of multi-coloured beads and thread them on a silver chain, the necklace you make will be original: an illustration of your taste and talent—or its absence.

If a hundred people make a necklace from the same set of beads, they will all be different. Some will be a mess, others mediocre, perhaps one a masterpiece.

Writing is like that. You have a lexicon of words and the writer must lay them out on a thread that is pleasing, compelling, rhythmic—luscious as honey poured from a jar. Bad writing is like garbage thrown into the street: noisy, careless, impossible to ignore.

So can you learn how to write?

Mozart was composing sonatas at the age of five, but he still had to learn how to play the piano. He did so on his father’s knee from the age of three. Mozart was taught how to coax notes from the keyboard, but the way he combined those notes came from something inside him.

Writing is the same. A teacher cannot teach you how to write. What a teacher can do is show you how not to write. Writers must find their own style, their own voice, their own way of interweaving words. The teacher is your first critic.

The way to find your voice is through rewriting: editing, cutting, scrapping, starting again. You know there is a story in your head; you just have to weave the threads together.

To borrow a sculptural metaphor, the great novel, essay, or biography is imprisoned inside a block of marble. The writer chips away with a tiny chisel until the exquisite appears.

Try this experiment. Write an eight-line paragraph describing a walk in the park. Then cross out every fourth word. If you need to put one back for the paragraph to make sense, remove another. Keep going until the same story survives with a quarter of the words deleted.

Now try this. Take a page you have written and read it aloud; record it on your phone. Then cross out every adjective and adverb and record it again. Listen to both versions. You will be shocked.

Never use the passive where you can use the active

The secretary mailed the letter.

The letter was mailed by the secretary.

In the first sentence, the secretary is the star and the sentence does away with that bothersome little “was”. In the second, the letter takes centre stage while the secretary fades. Usually the first is better—but sometimes the letter matters more, especially if it comes from a lawyer and contains news of a forgotten inheritance.